Introduction: Decoding Waldenstrom Macroglobulinemia

Waldenstrom Macroglobulinemia, often abbreviated as WM, is a term that might sound foreign to many. This rare blood cancer, originating from white blood cells, has piqued the curiosity of the medical world due to its distinctive characteristics and the challenges it presents in diagnosis and treatment. Understanding WM, its implications, and its management can be seen as a journey—a journey through the intricate fabric of the human body, exploring the complexities of our cells, proteins, and genetics.

There’s a certain unpredictability associated with WM. Unlike many other forms of cancer, its progression is usually slow, which can be both a blessing and a curse. A slower progression often means a longer duration of uncertainty, adaptation, and continuous monitoring. This uncertainty is compounded by the fact that the precise cause of WM remains elusive despite numerous studies.

On a brighter note, this slow progression provides medical professionals with a window of opportunity. Time is a precious asset in the world of healthcare, and in the case of WM, it allows doctors and patients to collaboratively design a tailored treatment approach, rather than rushing into aggressive interventions.

Yet, despite the challenges and mysteries surrounding it, there’s an undeniably strong will within the medical community and amongst patients to tackle WM head-on. This drive is fueled by continuous research, the shared experiences of patients, and the dedication of healthcare professionals.

Fact 1: What is Waldenstrom Macroglobulinemia?

Waldenstrom Macroglobulinemia, commonly abbreviated as WM, is more than just a mouthful of medical jargon. It represents a rare form of blood cancer that emerges from the white blood cells. A key characteristic of WM is the excessive production of a protein called macroglobulin. When present in high amounts, this protein impacts various bodily functions, leading to a cascade of symptoms that we’ll delve into later.

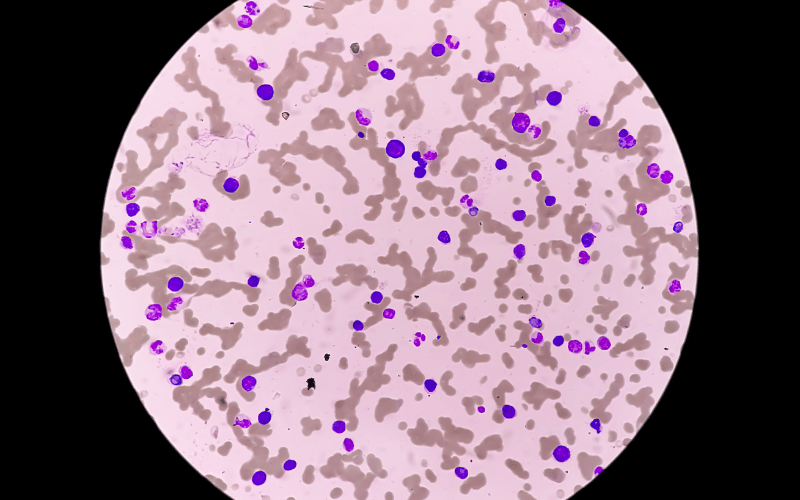

So, what makes WM particularly distinct? One reason is its origin. Unlike many cancers that stem from damaged or transformed cells, WM primarily originates from a specific type of white blood cell called B cells. These cells play a crucial role in the body’s immune response, producing antibodies to combat infections. In WM, these B cells become malignant, leading to the release of vast amounts of macroglobulin.

This overproduction of macroglobulin is far from harmless. It can thicken the blood, a condition medically termed as hyperviscosity. When the blood becomes too viscous, its flow is compromised, which can lead to various complications.

The presence of excessive macroglobulin isn’t just a blood issue. This protein can deposit in different organs, impacting their function. Over time, this can lead to organ damage, further complicating the patient’s condition. (1)